Clinical case studies play a vital role in reflecting on practice, supporting learning, and sharing best practice across healthcare. By exploring real patient journeys, they provide valuable insight into clinical decision-making, challenges encountered, and outcomes achieved. Case studies encourage reflective practice, support service improvement, and help clinicians learn from both successes and complexities, ultimately contributing to safer, more effective patient care.

Case Study 1

Endovenous Laser Ablation and Adjunctive Sclerotherapy

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a prevalent and progressive condition with significant clinical and socioeconomic implications. Although varicose veins are often perceived as a cosmetic concern, untreated superficial venous reflux can lead to chronic symptoms, skin changes and venous leg ulceration. Over the past two decades, management has shifted away from open surgery towards minimally invasive endovenous interventions, with endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) now established as first-line treatment for truncal reflux in appropriate patients.

This case study presents a clinically focused review of contemporary varicose vein management, supported by a detailed case study describing EVLA with adjunctive foam sclerotherapy. In addition to outlining venous anatomy, pathophysiology and current evidence-based guidance, the article follows the patient journey from assessment through treatment and recovery. A key feature is the inclusion of a longitudinal patient narrative, providing insight into symptom evolution, recovery milestones and the lived experience of endovenous intervention. The aim is to offer both a clinically grounded and patient-centred perspective on venous disease management, reinforcing the value of early recognition and intervention.

Who this article is for

This article is intended for healthcare professionals involved in the assessment, treatment or ongoing care of patients with venous disease, including:

- Vascular and interventional clinicians

- Tissue viability nurses and wound care specialists

- Community and district nurses

- General practitioners and advanced clinical practitioners

- Allied healthcare professionals with an interest in lower limb health

In addition, the inclusion of a detailed patient narrative makes this article relevant to members of the general public who are experiencing symptoms such as leg heaviness, aching, swelling or visible varicose veins. By describing the investigation process, treatment options and recovery in a clear and structured way, the article may help patients better understand their symptoms, what treatment may involve, and what to expect during recovery.

While the content is clinically informed, it aims to support shared decision-making by bridging clinical evidence with real-world patient experience.

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) represents a significant and often under recognised clinical burden in the United Kingdom. Varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency are highly prevalent conditions, affecting an estimated 20–40% of adults, with prevalence increasing with age, obesity, reduced mobility, and occupational risk factors such as prolonged standing (Beebe-Dimmer et al 2005, Marsden et al., 2015). While varicose veins are frequently misunderstood as a cosmetic concern, the clinical consequences can be substantial. Symptoms such as pain, heaviness, oedema, and eczema can progress to lipodermatosclerosis and venous leg ulceration (Fig.1), with profound effects on quality of life, mobility and functional independence (NICE 2020).

The wider context of chronic wound care in the UK further emphasises the importance of timely identification and management of venous disease. Updated analyses by Guest et al (2020) estimate that in 2017/18 the NHS managed approximately 3.8 million patients with a wound, a 71% increase compared with 2012/13. The annual cost to the NHS was estimated to be £8.3 billion, of which £5.6 billion was spent on wounds that failed to heal. Notably, over 80% of all wound care expenditure fell within primary and community services, with district nurses undertaking over 54 million visits related to wound management in that one year period. Venous leg ulcers, one of the most persistent and resource intensive wound types, contribute significantly to this burden, highlighting the need for effective pathways that address the underlying venous pathology rather than solely its consequences. Over the last two decades, the management of varicose veins has evolved considerably. Traditional surgical approaches, particularly high ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein (GSV), have been largely superseded by minimally invasive endothermal treatments, most commonly endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). These techniques are associated with faster recovery, reduced postoperative pain, and high long term occlusion rates compared with surgery (Nesbitt et al 2014, Brittenden et al 2019). Their adoption in UK practice has been strongly influenced by robust evidence and the publication of NICE Guideline NG168 (NICE, 2020), which recommends endothermal ablation as the first line intervention for truncal reflux, followed by ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), with surgery reserved for cases where neither technique is appropriate.

A major milestone in shaping modern venous practice was the UK led Early Venous Reflux Ablation (EVRA) trial. EVRA demonstrated that early endovenous ablation in patients with active venous ulceration results in faster healing and improved ulcer free time compared with compression therapy alone (Gohel et al 2018). This evidence marked a paradigm shift, treating superficial venous reflux early is not merely symptom relieving, it plays a crucial role in ulcer healing, prevention and recurrence reduction. Despite this, access to endovenous treatment remains inconsistent across the UK. Commissioning limitations, regional service variation and reliance on privately funded pathways mean that many patients experience delays in diagnosis and definitive management (Campbell et al 2017). Such delays increase the risk of disease progression, chronic skin changes and avoidable ulceration. EVLA and RFA for tributary varicosities offers an effective, minimally invasive and durable method of treating superficial venous reflux (Nesbitt et al 2014).

This case study provides an overview of the relevant anatomy and physiology, the contemporary evidence base underpinning the management of venous insufficiency and a detailed case study illustrating the use of EVLA and adjunctive foam sclerotherapy (AFS) for GSV reflux and associated tributaries. The aim is to contribute a clinically grounded and educational perspective that reinforces the importance of early disease recognition and the need for equitable access to definitive venous interventions across the UK.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Lower Limb Venous System

For clinicians working across vascular services, general practice, community nursing, and tissue viability, a sound understanding of venous anatomy, disease progression, and the principles underpinning early interventional management is essential. Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a common and progressive condition, and delays in recognition or referral can contribute to worsening symptoms, skin changes, and the development of venous leg ulceration. Timely assessment and appropriate intervention not only improve patient outcomes and quality of life but may also significantly reduce the long term healthcare burden associated with chronic venous ulceration.

A thorough understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the lower limb venous system underpins the effective diagnosis and management of CVD. Venous return from the lower limb is dependent on a complex interaction between venous structure, competent valvular function, the calf muscle pump, and respiratory dynamics. Disruption to any component of this system can result in venous hypertension and progressive venous pathology.

Anatomically, the venous system of the lower limb is broadly divided into the deep, superficial and perforating (communicating) veins, each fulfilling a distinct role in venous return and disease pathophysiology. The deep veins are responsible for the majority of venous return from the limb, the superficial veins primarily drain the skin and subcutaneous tissues and the perforating veins facilitate unidirectional flow between these systems. Understanding the organisation and function of these venous networks is fundamental to interpreting venous reflux, obstruction and the rationale for contemporary interventional strategies.

Deep Venous System

Deep veins lie beneath the strong, dense connective tissue layer known as the deep fascia. Most deep veins are arranged in pairs (venae comitantes), closely accompanying and following the course of corresponding arteries in the limb. This structure helps the veins transport blood efficiently, with arterial pulsations assisting venous return. The main deep veins of the lower limb are the anterior and posterior tibial veins, peroneal veins, popliteal vein, and femoral vein which together carry most of the blood returning from the leg to the heart against gravity. Because these veins must work against gravity, their patency and the integrity of their valves are essential for effective venous return. While the lymphatic system plays a crucial role in the return of interstitial fluid and proteins to the circulation, the deep venous system provides the principal pathway for venous blood return from the lower limb (Wittens et al 2015).

Superficial Venous System

The superficial veins lie within the subcutaneous tissue, outside the deep fascia. The GSV, the longest vein in the body, originates at the medial aspect of the dorsal venous arch of the foot, ascends anterior to the medial malleolus and travels along the medial aspect of the leg and thigh ending in the femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) (Callam 1994, Labropoulos et al 2003). The short saphenous vein (SSV) arises from the lateral dorsal venous arch, travels posteriorly along the calf, and drains into the popliteal vein behind the knee. Tributaries of the GSV and SSV are part of a network of superficial veins in the legs that commonly develop varicosities, especially in CVD. The Giacomini vein, also known as the inter-saphenous vein, serves as an anatomical connection between the SSV and the GSV, typically coursing along the posterior thigh. Its presence is variable, but when present, it can act as a pathway for venous reflux or varicosity formation, particularly in cases of chronic venous disease. Recognising the Giacomini vein and its potential involvement is clinically relevant, as it may influence both the diagnosis and management of superficial venous insufficiency, especially when planning interventions such as EVLA and RFA.

Perforating Veins

Perforating veins play a crucial role in connecting the superficial and deep venous systems of the lower limb. These veins act as conduits, directing blood flow from the superficial veins situated within the subcutaneous tissue to the deeper veins located beneath the deep fascia. The unidirectional flow through perforators is maintained by functional valves within these vessels, which helps to ensure that blood moves efficiently towards the deep system and, ultimately, back to the heart (Labropoulos et al 2003).

Venous Valves and the Calf Muscle Pump

Further to the above, venous return from the lower limb is supported by bicuspid valves that prevent blood from flowing backwards. Working together with the calf muscle pump, these valves help blood move upward against hydrostatic pressure when a person is standing. Importantly, these valves are strategically situated throughout all levels of the venous system, including the superficial, deep and perforating veins in order to maintain unidirectional blood flow towards the heart. Their consistent presence ensures that, regardless of the vein or its anatomical location, blood is effectively propelled upwards and pooling is minimised, thus reducing the risk of venous hypertension and related complications. With each calf muscle contraction, the deep veins are compressed and blood is pushed centrally, while competent valves stop it from reflux (Nicolaides et al 2018).

System failure

When venous valves become incompetent, perforating veins may permit abnormal reverse blood flow from the deep to the superficial system. This reversal elevates venous pressure within the superficial veins, a phenomenon termed venous hypertension. The resulting increase in pressure can lead to the development of varicosities and skin changes, hallmark features of chronic venous disease (CVD). System failure, whether due to valve incompetence, venous obstruction, or impaired calf muscle pump function, further exacerbates venous hypertension. This, in turn, drives the progression of clinical manifestations including varicose veins, oedema, skin changes, and ultimately venous ulceration. Additionally, chronic venous hypertension may cause dilation of major superficial veins such as the great saphenous vein (GSV) or short saphenous vein (SSV). This dilation is often evident on duplex ultrasound and is a key indicator in the pathophysiology of chronic venous insufficiency, contributing to the progression from asymptomatic reflux to more advanced complications such as heaviness, aching, further skin changes, and ulceration (Eklöf et al 2004).

Clinical Relevance

Accurate knowledge of lower limb venous anatomy and physiology underpins both diagnostic assessment and interventional planning. It is essential for interpreting Doppler and Duplex ultrasound mapping and for planning procedures such as EVLA. Precise localisation of truncal reflux, identification of competent and incompetent perforators, and mapping of tributary varicosities are key to achieving good clinical outcomes and reducing the risk of recurrence (NICE 2013).

Classification of Chronic Venous Disease: CEAP

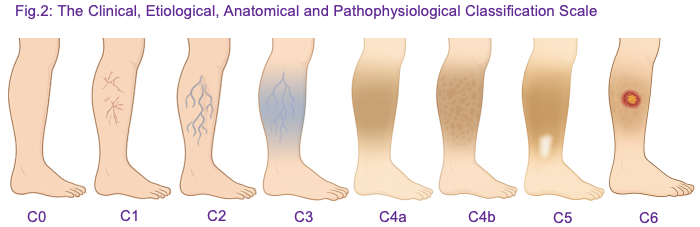

Accurate classification of CVD is essential for consistent assessment, treatment planning, and outcome measurement. The Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical and Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification, first introduced in 1994 by a joint committee of the American Venous Forum and the Society for Vascular Surgery, was first formally published in 2004, providing a structured framework to categorise venous disorders based on Clinical, Etiologic, Anatomic, and Pathophysiologic criteria (Eklöf et al 2004). Prior to CEAP, terminology describing varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency was inconsistent, often combining subjective symptom descriptions with variable anatomical definitions, which made comparison across studies and audit of interventions challenging. CEAP addressed this gap by offering a multidimensional system to standardise assessment and reporting.

The clinical component of the CEAP classification ranges from C0 to C6 and provides a structured framework for documenting chronic venous disease severity (Fig. 2). C0 denotes the absence of visible or palpable signs of venous disease. C1 includes telangiectasias or reticular veins measuring <3 mm in diameter, while C2 represents varicose veins ≥3 mm in diameter. C3 is defined by the presence of oedema without skin changes. Progressive skin changes are captured in C4, subdivided into C4a (pigmentation or venous eczema) and C4b (lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche). Patients with healed venous ulceration are classified as C5, whereas those with active venous ulceration are classified as C6. This classification enables consistent documentation of disease severity, monitoring of progression, and assessment of response to interventions such as EVLA, RFA and AFS (Eklöf et al., 2004).

In 2020, an international consensus update refined CEAP to reflect advances in diagnostic imaging, minimally invasive interventions, and contemporary clinical practice (Lurie et al 2020). The update emphasised the use of duplex ultrasound for objective anatomical and functional assessment, encouraged integration of patient reported symptoms into evaluation, and provided greater granularity in the description of truncal veins, tributaries and perforators. It also recommended routine documentation of CEAP classification in electronic records to support audit, research and standardised reporting. These refinements ensure that CEAP remains relevant in the era of endovenous therapies, allowing practitioners to identify suitable candidates for intervention, guide treatment planning and evaluate post procedural outcomes.

Endovenous Laser Ablation (EVLA): What, When and How

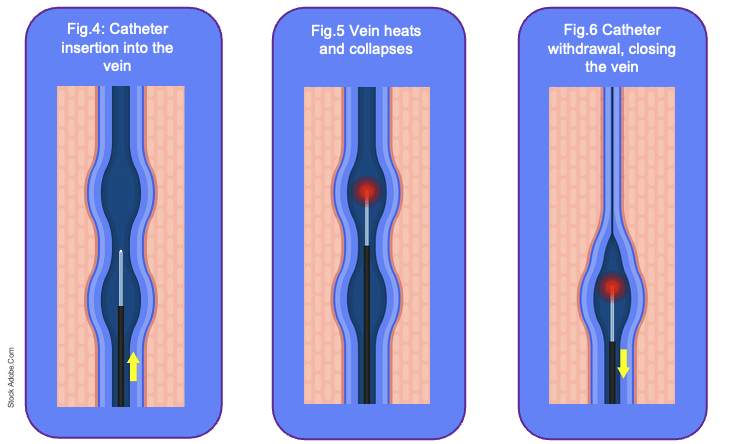

EVLA is a minimally invasive technique for treating symptomatic superficial venous reflux, most commonly involving the GSV or SSV. EVLA works by delivering laser energy via a fibre inserted into the vein under ultrasound guidance, causing thermal injury to the endothelium and subsequent vein closure (Fig.3). Occlusion of the incompetent vein reroutes blood flow through competent deep and perforating veins, relieving venous hypertension, reducing symptoms and preventing progression to skin changes and ulceration (Gohel et al 2018, Nesbitt et al 2014).

How EVLA is Performed

Ultrasound mapping of the affected limb is the first step in the process. This technique pinpoints the target vein segment, verifies the location and severity of reflux and highlights the entry sites needed for the procedure. This mapping session is not only a technical assessment but also serves as a detailed consultation with the patient. During this visit, the clinician explains the underlying pathophysiology of the venous reflux, demonstrating how venous incompetence lead to venous hypertension, varicosities and potential skin changes or ulceration. The mapping appointment also provides an opportunity to discuss all appropriate treatment options, including EVLA and where necessary, UGFS for tributary veins. Patients are informed about what the procedure involves, including the use of local anaesthesia, tumescent fluid and the application of post procedure compression. This also includes the likely short term outcomes such as bruising, mild discomfort and temporary oedema. Longer term expectations are also addressed, including improvements in symptoms, cosmetic appearance and the reduction in risk of ulceration or recurrence. Once all details have been thoroughly explained and questions addressed, a planned date for the procedure is agreed, and written consent is obtained in line with UK clinical governance and medico legal standards (NICE 2020).

The majority of clinics perform EVLA using local anaesthesia, which allows the patient to remain awake while the treatment area is numbed. In certain centres, sedation may be offered; however, this option is typically more costly for the patient. EVLA is generally delivered as a day case procedure, enabling patients to go home soon after. During the procedure, tumescent fluid is injected around the vein to enhance anaesthesia, facilitate vein compression for optimal closure, and protect adjacent tissues from thermal injury caused by the laser (Nandhra et al 2018).

A percutaneous puncture allows introduction of a laser fibre to the optimal position determined by ultrasound guidance, which may vary depending on the extent of reflux and the planned segment of vein closure (Fig.4). In some patients, this may be just distal to the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction, while in others, such as those requiring complete GSV closure, the fibre may be inserted further distally to safely achieve full treatment of the incompetent segment. Tumescent anaesthesia, delivered along the vein provides local anaesthesia, compresses the vein around the fibre and protects surrounding tissues from thermal injury (NICE 2020).

The laser is then activated and the fibre withdrawn at a controlled rate, producing uniform thermal closure along the length of the vein (Fig.5-6).

Following ablation, adjunctive treatments such as UGFS can be used to treat residual tributaries and smaller varicosities that were not directly addressed by the main EVLA procedure (Gupta et al 2020). In practice, these veins often represent the smaller branches connected to the treated truncal vein and may remain visibly dilated or symptomatic even after successful ablation. As observed in our case study, these veins were treated with UGFS shortly after the main EVLA procedure. It is standard practice to reassess the treated veins, usually at an interval of 6 to 8 weeks after the initial procedure. This follow up period allows the clinician to check complete superficial vein occlusion has been achieved. If any residual or recurrent veins are identified during this assessment, additional sclerotherapy is usually repeated to address these areas. This repeat treatment is often necessary because initial sclerotherapy may not completely obliterate all small channels and veins that were previously under high pressure can dilate once the truncal reflux is eliminated, allowing foam to be more effective and reduces the risk of recurrence.

Indications and Patient Selection for EVLA in the UK

Patient selection in the UK is guided by clinical severity, symptoms, and imaging confirmation of truncal reflux. According to NICE guidance NG168, EVLA is indicated for patients with symptomatic varicose veins (CEAP C2-C6) where duplex ultrasound confirms reflux in a truncal vein, including the GSV or SSV (NICE 2020). The procedure is considered a first line approach over traditional surgery because of its minimally invasive nature, shorter recovery, reduced post procedural pain, and comparable long term vein closure rates (Brittenden et al 2019). EVLA may also be prioritised in patients with healed or active venous ulcers (CEAP C5-C6), as evidence from the EVRA trial demonstrates that early ablation accelerates ulcer healing and increases ulcer free time (Gohel et al 2018).

Advantages and Considerations

EVLA is generally regarded as a safe and well tolerated procedure, with a favourable safety profile and low rates of complications. Although the risk of serious adverse events is rare, potential complications include endothermal heat induced thrombosis (EHIT), nerve injury or skin burns (Nesbitt et al 2014). These occurrences are uncommon, and the majority of patients experience an uneventful recovery. Most individuals undergoing EVLA benefit from a relatively swift recovery period, typically resuming their normal daily activities within a few days following the procedure. Post procedure care is an essential aspect of the treatment pathway and includes the application of compression therapy to support vein closure and healing, encouragement of early mobilisation to promote effective venous return, and scheduled follow up duplex scanning to confirm successful closure of the treated vein. Within the United Kingdom, EVLA has been widely adopted as a standard intervention in both NHS and private vascular services. However, it is important to note that there remains some regional variability in access to this treatment, often influenced by differences in local commissioning policies and service availability (Campbell et al 2017).

Service availability

According to the Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Integrated Care Board (LLR ICB) policy, NHS funded treatment for varicose veins, including EVLA, UGFS or surgical stripping is only provided when the patient meets specific clinical criteria. These include the presence of varicose eczema, lipodermatosclerosis or an active or healed varicose ulcer, at least two documented episodes of superficial thrombophlebitis or a major bleeding event from the varicosity. These criteria correspond to CEAP stage C4 or above. Patients with milder disease (CEAP 2 to 3), without such complications, are generally not eligible for interventional treatment on the NHS and instead are offered conservative management such as compression hosiery and lifestyle advice. However, if their condition progresses and meets the criteria later, they may be referred for treatment at that time. This policy states resources are prioritised for patients with significant clinical need, consistent with NICE guidance and local commissioning practices (LLR ICB 2024).

Case Study: Introduction

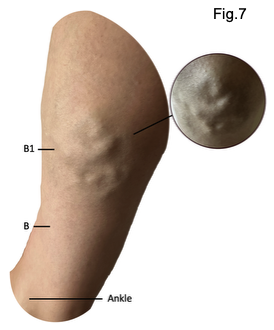

This case study examines a healthy and active 41 year-old female with no known comorbidities. However, the patient has progressive bulging tributary veins situated between the B and B1 measurement points of the medial right lower limb. The onset of her venous symptoms can be traced back to 2011, following a full term twin pregnancy. The pregnancy necessitated a planned caesarean section because of a breech presentation and likely resulted in considerable intra-abdominal pressure during the third trimester. This increased pressure may have led to venous stasis, venous hypertension, and a higher risk of superficial venous reflux (Beebe-Dimmer et al 2000, Gloviczki & Comerota, 2017). As is common in pregnancy, alterations in gait and periods of flat footed ambulation may have reduced the efficiency of the calf muscle pump, a key mechanism for lower limb venous return (Nicolaides 2018). Her occupation as a marketing manager, involving prolonged sitting, may have further limited intermittent muscle contraction and compounded venous hypertension. These mechanical and behavioural factors were accompanied by physiological influences. Elevated oestrogen levels during pregnancy increase venous wall distensibility and can promote reflux in susceptible superficial veins (Gloviczki & Comerota 2017, Eklöf et al 2004). There is also a family history of varicose veins, indicating a hereditary risk for valve dysfunction and vein wall weakness (Evans et al 2003, Beebe-Dimmer et al 2005). Together, these converging genetic, mechanical, and hormonal factors likely contributed to the development of superficial venous incompetence and subsequent venous hypertension, undermining both the function and structural integrity of the superficial venous system.

Although there were no immediate or obvious clinical signs of venous incompetence following her 2011 twin pregnancy, the patient began to notice gradual and progressive changes in the years that followed. Initially, these changes were predominantly cosmetic, with the appearance of more prominent veins becoming increasingly noticeable over the course of the subsequent decade. This progressed from subtle aesthetic changes to visible vein prominence and occasional heavy, aching legs, characteristic of early superficial venous insufficiency. It represented an early indicator of underlying venous dysfunction that would later become more clinically significant. Over time, progressive evidence of venous reflux was observed in the residual tributaries corresponding to the B and B1 measurement points along the medial upper gaiter region and distal calf. These veins gradually became more distended and extended in surface area, consistent with chronic venous hypertension and progressive superficial venous dilation (Fig.7). More recently, the patient observed a visible and palpable swelling in the proximal segment of the great saphenous vein, particularly in the mid-thigh region. This finding suggests that the venous reflux, which was initially observed in the distal tributaries, affected more of the truncal vein, pointing to a likely primary source of reflux.

Clinical Progression

During the 18 months prior to a vascular assessment, she had begun wearing a compression sports sleeve during running, initially for psychological reassurance but also with the intention of supporting venous return during exercise. She maintained an ongoing high level of physical activity, running 5 to 7 km every morning. At this stage, symptoms were more aesthetic than functionally limiting, although she had become increasingly aware of the gradual progression in vein prominence. A key turning point occurred during a short haul flight to Portugal, during which she experienced marked aching and heaviness, specifically in the right lower leg where the tributaries were most distended. By the early hours of the following morning, symptoms had intensified, presenting as numbness, discomfort and difficulty weight bearing. These symptoms resolved over 24 to 48 hours with continued use of her sports compression sleeve and active movement, allowing her to resume her usual running routine. Upon returning to the UK, she attempted to use in flight compression in an attempt to reduce the risk of symptoms returning, however, on return this resulted in a significant swelling, warmth and deep discomfort in the right lower limb. Although these symptoms again resolved with limb elevation and compression, she became increasingly concerned that this presentation may have represented a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). In response, she contacted her local private clinic to seek formal assessment, diagnosis and advice regarding further management options.

Vascular Assessment

The patient scheduled a private vascular assessment at a nationally recognised venous centre (Vein Centre) to receive a comprehensive evaluation and discuss long term treatment options suited to her needs. A comprehensive vascular assessment formed the foundation of the patient’s diagnostic work up. The consultation began with a detailed discussion to explore her medical history, symptom progression and aesthetic concerns. This patient centred approach is increasingly recognised as an essential component of venous care as symptoms of CVD often vary markedly between individuals and do not always correlate with visible clinical severity (Kakkos et al 2020). By fostering open communication and allowing sufficient time for questions, the consultant addressed the patient’s goals and concerns, particularly regarding deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and long term consequences of not treating CVD. The consultant explained that interventions for varicose veins, such as endovenous ablation, carry a very low risk and conversely, reduces the long term risk of complications. Moreover, acting early and selecting the appropriate treatment can help prevent serious complications of varicose veins, such as thrombosis, skin changes and leg ulceration (Chang et al 2021).

Duplex Ultrasound Examination

A duplex ultrasound scan was performed while the patient was standing, the gold standard method for diagnosing venous reflux and mapping patterns of incompetence (NICE 2020, ESVS 2022). Scanning in the upright position allows gravitational pressure to distend superficial veins and reveal abnormal retrograde flow, making it significantly more sensitive for detecting valvular failure than supine assessment. The scan was quick, painless and non-invasive, yet critically informative (Fig.8). Duplex ultrasound provides real time visualisation of:

- Venous anatomy: Including truncal veins, tributaries, and perforators.

- Valve competence: Identifying segments where reflux occurs.

- Flow direction and duration: Where pathological reflux is defined as retrograde flow lasting >0.5 seconds in superficial veins (ESVS 2022).

This level of detail is essential because many patients with visible varicose veins have underlying truncal reflux that is not clinically detectable (Labropoulos et al 2000). As in this case, the duplex findings revealed that the primary source of venous incompetence was at the proximal truncal segment of the right GSV.

Clinical Interpretation and Treatment Recommendations

The consultant provided an immediate explanation of the scan results, allowing the patient to gain a clear understanding of the anatomical origins of her symptoms. This direct communication helped to bridge the gap between clinical findings and patient experiences, ensuring that the underlying causes of her discomfort and aesthetic concerns were made explicit.

Following this discussion, the consultant outlined a tailored management strategy, informed by the duplex ultrasound findings and the patient’s clinical presentation.

The proposed plan included:

- Complete occlusion of the incompetent GSV using EVLA, in line with current NICE guidance advocating endothermal ablation as the first line treatment for truncal reflux (2020).

- UGFS, targeting the dilated tributaries in the medial gaiter region.

It is important to recognise that UGFS may need to be repeated approximately 6 to 8 weeks after the initial treatment. This need for repetition arises because residual veins can persist, or new small channels may become apparent once the truncal pressure has been effectively eliminated. Such occurrences are a common and well recognised aspect of staged venous intervention, as highlighted in the literature (Cavezzi et al 2018).

This staged strategy is consistent with modern evidence based practice in the management of venous reflux. The recommended approach is to first treat the primary source of reflux, typically the incompetent truncal vein, and then once haemodynamic correction has been achieved, proceed to address any remaining tributary varicosities. This sequential method ensures that the underlying cause of venous insufficiency is managed before further interventions are undertaken to treat visible or symptomatic tributaries (Gloviczki & Comerota, 2017).

The patient was advised that ultrasound findings remain clinically valid for approximately six months, beyond which repeat scanning may be required if symptoms or vein appearance change, as CVD can progress with time. Early booking was therefore recommended to ensure timely intervention, reduce further deterioration of the gaiter tributaries, and minimise the risk of complications such as inflammation, pigmentation or more advanced venous disease.

Treatment Decision and Planned Interventions

Although the patient expressed some initial hesitation, she consented to proceed with the recommended management plan. The primary intervention is EVLA of the GSV, targeting the incompetent truncal segment identified on duplex ultrasound. This minimally invasive procedure was chosen to achieve complete occlusion of the affected vein, thereby correcting the anatomical basis of her venous reflux.

Alongside EVLA, UGFS will be administered to the dilated tributaries in the medial gaiter region. This adjunctive treatment is intended to address the visible varicosities and help alleviate related symptoms, such as swelling and discomfort, by closing the affected superficial veins and promoting haemodynamic improvement.

Procedure

The procedure lasted approximately 60 minutes. The patient was positioned supine, and prior to cannulation or any skin puncture, the consultant re-examined the limb using real time duplex ultrasound to reconfirm anatomical landmarks and the exact course of the incompetent segment of the GSV (Fig.9).

Before beginning the procedure, the consultant ensured the patient had the opportunity to ask any questions or raise any concerns. This open dialogue was designed to address any uncertainties and provide reassurance regarding the planned interventions. The consultant explained that while patients might notice some initial discomfort as the local anaesthetic takes effect, there should be no pain during the EVLA itself. This clarification aimed to alleviate anxiety about procedural pain and set realistic expectations for the experience.

Additionally, the consultant informed the patient that some individuals report an unusual taste, often described as ‘garlic like’ during the early stages of treatment. This sensory phenomenon, although not universal, was mentioned to ensure the patient was fully prepared for all potential sensations that could arise during the procedure (VeinCentre 2025).

Prior to venous cannulation, local anaesthetic was infiltrated at the planned access site to facilitate comfortable ultrasound guided entry into the great saphenous vein (GSV). Under continuous ultrasound guidance, percutaneous access to the target vein segment was obtained using a hollow introducer needle. A guidewire was then advanced through the needle and positioned within the refluxing segment of the vein, with intraluminal placement confirmed sonographically. Once correct intraluminal placement was confirmed, a thin, flexible catheter was introduced over the guidewire and advanced to the planned treatment level. The guidewire was subsequently removed, and the laser fibre was inserted through the catheter and positioned at the appropriate starting point for ablation. Tumescent anaesthesia was then infiltrated along the length of the target vein to provide analgesia, create a protective thermal buffer, and ensure adequate vein wall apposition around the catheter. Laser heat was then delivered segmentally as the catheter was gradually withdrawn, resulting in controlled endothelial damage, collagen contraction and subsequent vein closure (Fig.10).

Throughout the procedure, real time duplex ultrasound confirmed correct catheter positioning, successful vein wall contact and the absence of immediate complications. The patient tolerated the procedure well overall, with some sharp pain noted whilst the anaesthetic took effect. As previously discussed, the patient did experience a garlic like taste at the start of treatment; however, this sensation lasted only for the first five minutes before resolving completely. Importantly, there were no other significant adverse effects noted during the procedure, and the patient remained comfortable throughout.

Adjunctive Sclerotherapy

Following thermal ablation, residual superficial tributaries were assessed. These veins that frequently remain after the primary source of reflux has been treated, are a common finding and can contribute to persistent symptoms or cosmetic concerns. In this case, UGFS was used to address several remaining tributaries. Foam sclerosant is advantageous because its increased surface contact and slower dilution enhance endothelial disruption, promoting fibrosis and vein obliteration (Gupta et al 2020). This causes the vein walls to collapse and adhere, after which the body gradually breaks down and reabsorbs the treated vein. This procedure took approximately 15 minutes and again was well tolerated throughout. At the conclusion of the procedure, a small dressing was applied over the needle acess site, and a pre measured, British Standard Class 2, full length compression stocking was fitted. Guidance was provided to leave the stocking in situ for 7 days, followed by a further week of daily replacement with a newly washed garment, although patients may continue longer if found more comfortable.

Anticipated Post Treatment Symptoms and Physiological Changes

The consultant took time to outline the range of post treatment symptoms the patient might experience, as well as the expected physiological changes during the vein absorption process. She was advised that, as the treated veins are gradually absorbed by the body, sensations of tautness or tightness along the length of the vein are common. The consultant also described that mild bruising could occur, sometimes presenting as a deeper purple discoloration in certain areas, though this would fade over time.

In terms of discomfort, the patient was informed that mild pain might be experienced, particularly in the first week to ten days following the procedure. This pain is typically manageable with standard analgesics. The consultant explained that a small increase in discomfort may be noticed around 7 to 10 days after treatment, corresponding to the phase when the body is actively breaking down and reabsorbing the treated veins. Importantly, the consultant reassured the patient that any symptoms previously associated with her varicose veins should resolve as the treated veins are absorbed. A significant improvement was anticipated by the time of the first follow up appointment, scheduled for approximately 6 to 8 weeks post procedure.

On conclusion, the team encouraged her to resume normal activity and running could commence, if tolerated, in 2 to 3 days. However, swimming is restricted while wearing the compression garment, and strenuous activities such as heavy weightlifting are discouraged until advised by the consultant. On discharge, she was encouraged to walk briskly for 20 minutes post procedure to encourage blood flow through deep veins and in turn reduce the risk of DVT. Driving is not permitted on the day of the procedure due to the infiltration of local anaesthetic which may affect overall limb function, thereby compromising driving ability. For air travel, short haul flights are permitted, however, long haul flights (>4 hours) should be avoided for 4 weeks post procedure.

Next Steps and Follow Up

As previously highlighted, it is clinically recognised that adjunctive sclerotherapy may need to be repeated, typically around 6 to 8 weeks after the initial procedure. This is because not all targeted tributaries or branching veins may fully occlude after the first injection, particularly if they are larger, tortuous, or if venous spasm temporarily limits sclerosant penetration. Additionally, previously non visible tributaries may become apparent once the primary refluxing trunk has been closed. Staged follow up sclerotherapy enables more complete clearance of the superficial venous network, optimises cosmetic outcomes and ensures that any residual reflux is effectively treated (Cavezzi et al 2018, Gupta et al 2020).

The patient received clear guidance regarding the importance of post procedural monitoring. She was advised to schedule a follow up appointment in approximately 6 to 8 weeks. At this review, a further duplex ultrasound scan would be performed to evaluate the treated veins, ensuring that the EVLA had effectively addressed the underlying venous reflux. This follow up assessment also serves to determine whether additional UGFS is required to treat any remaining varicosities. Such supplementary intervention may be necessary, particularly for cosmetic improvement, if residual veins persist. The patient was therefore advised to bring her compression hosiery to the appointment, as it would need to be worn again should further sclerotherapy be indicated.

24 Hours Post Procedure

In the first 24 hours after EVLA and sclerotherapy, the patient reported mild pain, tightness, heaviness along the ablation tract, and a dull ache in the medial calf. Despite these symptoms, pain relief requirements were minimal; only two paracetamol tablets were taken on the evening of the procedure, with no need for further analgesia overnight. The patient adhered to the post procedural instructions regarding compression, wearing full length compression hosiery continuously. Tolerance of the hosiery was reported as good; however, it was observed that an initial adjustment period was required to become accustomed to the silicone welt, which is designed to prevent garment slippage. On the morning following the intervention, minor bleeding was noted at the catheter insertion site (Fig.11).

Accordingly, the hosiery was rolled down to remove the small dressing. As no further bleeding was observed, reapplication of the dressing was deemed unnecessary, and the hosiery was promptly repositioned.

Mobility was maintained without difficulty during the first full day post procedure, with the patient able to walk independently and without restriction. There was no evidence of excessive swelling, erythema, or any signs suggestive of infection.

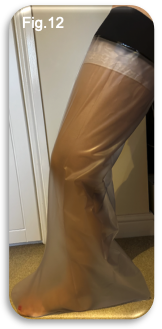

To facilitate showering while preserving the integrity of the compression hosiery, the patient made effective use of a Limbo® waterproof sleeve, preventing the garment from becoming wet (Fig.12).

Patient Narrative

“For the remainder of the day following the procedure, I took two paracetamol tablets that evening, primarily as a precaution in case pain developed, rather than due to any immediate discomfort”.

“My first night after the procedure was comfortable and mostly pain free. I noticed some tightness and heaviness in my treated leg, but it wasn’t especially painful. I can definitely feel the area where the laser went, especially in the thigh area. Walking gently around the house provided noticeable relief, helping to ease that tight sensation in my leg. The compression hosiery feels snug but not uncomfortable and I have been adjusting to it better than expected. At this early stage, bruising is minimal, though I anticipate this will develop over the coming days. Overall, I feel a sense of relief that the procedure is behind me and I’m relieved the procedure is over and curious to see how my leg feels over the coming days”.

48 Hours Post Procedure

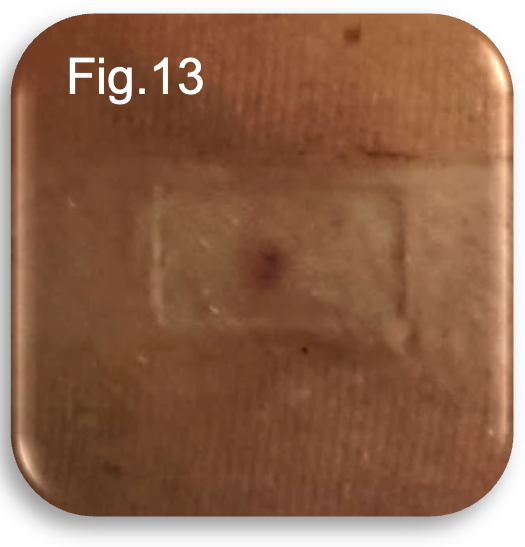

At 48 hours post procedure, the patient reported some deep tissue aching within the thigh, accompanied by a mild restless sensation localised to the lower medial aspect of the leg, consistent with expected post EVLA and post UGFS inflammatory changes. No further bleeding was noted. On examination, the catheter insertion site remained visible with a faint dressing demarcation; however, there was no erythema, heat, or discharge to suggest infection or delayed healing (Fig.13).

Bruising had begun to develop along the treated thigh region and within the lower medial gaiter, demonstrating typical early post treatment progression (Fig.14-15). Despite the emerging tenderness and discolouration, the patient’s mobility remained unaffected. The patient was able to ambulate normally and even perform a short run without experiencing pain, instability or functional limitation. Compression hosiery continued to be worn uninterrupted, and no complications were identified.

Patient Narrative

“I had another reasonably comfortable night, though there was some positional discomfort and tightness. I notice a deeper aching in the thigh today, definitely more than the first day but still very bearable and I have not needed to take any pain relief. Walking felt completely fine, and I even managed a small run without any issues. Bruising has now become visible on both my thigh and lower leg; however, this development is in line with what I was expecting at this stage of recovery, so I am not concerned”.

7 days Post Procedure

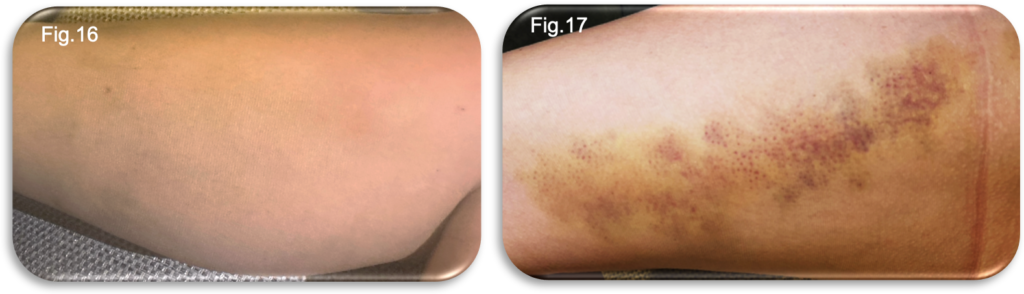

At seven days post procedure, bruising along the lower medial aspect had dispersed significantly and was now less prominent (Fig.16). In contrast, bruising within the thigh region had continued to deepen, displaying the expected evolution of post EVLA tissue changes (Fig.17). Discomfort in the lower medial aspect of the limb had improved; however, the patient reported increasing tightness and deeper tissue discomfort within the upper thigh. These symptoms were predominantly noticeable during the evening and overnight, aligning with typical diurnal variability in a post procedural inflammatory response.

Despite these sensations, there were no mobility limitations. The patient remained fully active and had been able to continue her running routine without requiring any analgesia. A hosiery failure was noted when a hole appeared in the stocking, and a repeat order for the same compression garment was arranged. Although permitted to remove the hosiery at night, the patient found this increased discomfort and tightness, therefore chose to continue wearing it continuously, replacing it with a clean stocking each morning after showering. During the review, a clear indentation was observed on the skin, corresponding to the location of the silicone welt (Fig.17). This demarcation indicated that sustained pressure from the welt had caused this marking. To minimise the risk of discomfort and to prevent potential skin trauma, the position of the silicone welt was adjusted periodically throughout the day whenever feasible. Regular repositioning was intended to alleviate localised pressure, thereby supporting skin integrity during the recovery period. No signs of infection, excessive swelling or concerning inflammation were identified at this review point.

Patient Narrative

“It’s now a week since the procedure, and the bruising on my thigh looks darker, but the bruising lower down the leg has faded a lot. In the evenings and at night, I notice that the tightness and deep aching in my thigh becomes more intense, although these feelings are much more manageable during the day. The treated vein feels like a tight rope under the skin, a feeling the consultant did say is typical of occluded tributary veins following the procedure. I can also feel some lumps and bumps along the vein, which I’ve been reassured is very common, and this nodular feeling can sometimes last for several months, or even up to a year. These symptoms seemed to follow a daily rhythm, with discomfort creeping in later in the day and overnight. Walking around regularly really helps ease that tight, achy feeling. Fortunately, when I’m on voice only meetings, I’m able to move about freely, which makes a noticeable difference in my comfort throughout the day”.

“I’ve been able to keep running, which is great, although it has felt harder than usual, it’s exactly what I expected at this stage. I don’t need any painkillers, which is reassuring. The calf bruising has reduced, but I can still feel lots of lumps and bumps under the skin where the foam was injected. I was told this might take a little while to settle and I may need more foam injections at my review in six weeks”.

“My stocking did fail when a hole appeared, so I’ve ordered a replacement. I tried sleeping without it, but it actually felt more uncomfortable, so I’m wearing it day and night and changing it after my shower each morning. I noticed some minor irritation around the area where the silicone welt sat against my skin. To help with this, I made a point of repositioning the silicone welt regularly throughout the day. In general, my recovery has been progressing as expected, although I have to admit the pain and tightness in my thigh has been a little more painful that I thought it would be”.

2 weeks Post Procedure

At fourteen days post procedure, the patient reported that, despite not requiring any analgesia, the preceding week had been the most symptomatic to date. Persistent tightness and deep aching within the thigh, particularly noticeable towards the end of the day and overnight, remained the predominant symptoms. These are consistent with the expected inflammatory and fibrotic changes occurring along the treated vein during this stage of recovery.

The patient continued to wear full length compression hosiery at all times. Although permitted to remove it overnight, previous attempts to do so had resulted in increased discomfort, necessitating continuous wear. The patient remained fully mobile, with no significant gait disturbance, and continued her running routine without limitation.

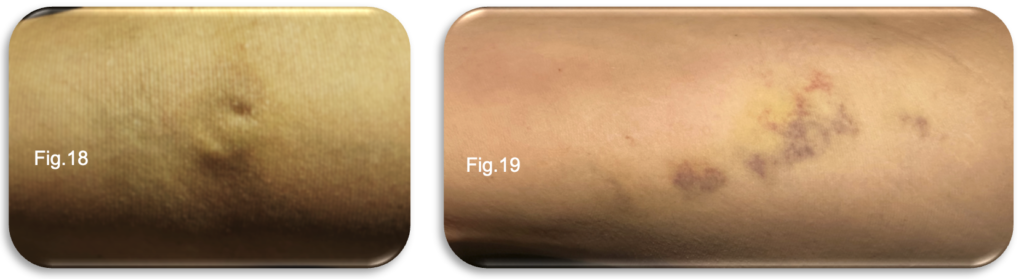

Bruising across the thigh and medial lower limb showed ongoing improvement, with day to day fading observed; however, residual discolouration remained visible, especially in the thigh (Fig.18-19). During the review of the medial gaiter region, a notable reduction in the size and visibility of the original tributaries was observed.

This improvement reflects the anticipated response to the EVLA and UGFS procedures, with significant fading of the previously prominent veins within this area. However, attention was drawn to a central zone where firmness had become increasingly apparent. The marked induration in this specific region suggests a localised tissue response, possibly related to post procedural inflammation or ongoing fibrotic changes within the treated veins. Palpation revealed a more defined, firm cord like structure along the ablation pathway, particularly within the thigh, consistent with normal vein contraction and fibrosis following EVLA. Walking periodically throughout the day, as advised, continued to alleviate tightness and restlessness within the limb. No signs of infection, concerning erythema or abnormal swelling were identified.

Patient Narrative

“It’s now two weeks since the procedure, and although I haven’t needed any painkillers, this past week has definitely been the most uncomfortable. The tightness and deep aching in my thigh are always worse in the evenings and overnight. I tried again to sleep without the stocking, but it was still more uncomfortable, so I’ve kept it on day and night”.

“Despite the discomfort, I’ve been able to keep running, which I’m really pleased about. Walking during the day makes a big difference to the tight and restless feeling in my leg, which is definitely worse at in the evening and at night. The bruising is improving every day, although it’s still very visible. I can now actually see and feel the treated vein, it feels tighter and more cord like, especially in the thigh. I was expecting this, but it’s still quite noticeable. Overall, things feel like they are slowly progressing, just with a bit more discomfort than the week before”.

3 weeks Post Procedure

At three weeks post procedure, the patient continued to report satisfactory progress with no requirement for analgesia. Bruising had further decreased and was now significantly lighter, with the most notable improvement observed within the thigh region. Early signs of mild hyperpigmentation (“staining”) were visible along the medial aspect of the lower limb, predominantly central to where the tributary varicosities had been treated. This finding is a normal and expected consequence of vein collapse and erythrocyte breakdown following both EVLA and UGFS, often resolving gradually over several weeks to months.

Compression hosiery continued to be worn continuously, as the patient continues to report this remains beneficial in reducing restlessness and deep aching, particularly towards the end of the day and overnight. The treated vein remained palpable as a firm cord like structure along the thigh, consistent with ongoing fibrosis and involution of the ablated vein.

From a functional perspective, the patient remained unrestricted in her daily activities following the procedure. However, she observed a slight adjustment in her walking style, adopting an uncharacteristic gait that enhanced comfort during ambulation. Despite this compensatory change, her ability to run was unaffected, and she continued her running routine without difficulty. Notably, running was described as feeling progressively easier as the overall level of discomfort in the limb subsided over time. No erythema, heat or signs of infection were present, and overall progression remained in line with expected clinical healing trajectories.

Patient Narrative

“Three weeks on and I still haven’t needed to take any painkillers at all. The bruising is fading really nicely now, especially around my thigh, where it’s much lighter than before. I’ve started to notice a bit of brownish staining on the inside of my lower leg where the tributary veins were treated, but I was reassured this is completely normal as the veins collapse and heal”.

“I’ve kept wearing the stocking day and night because it genuinely helps with the restlessness and aching, especially in the evenings and overnight. The tight feeling in my thigh is still there, but it’s becoming less bothersome. I’ve been able to keep running, and it’s actually starting to feel easier as time goes on. Overall, everything seems to be moving in the right direction”.

5 weeks Post Procedure

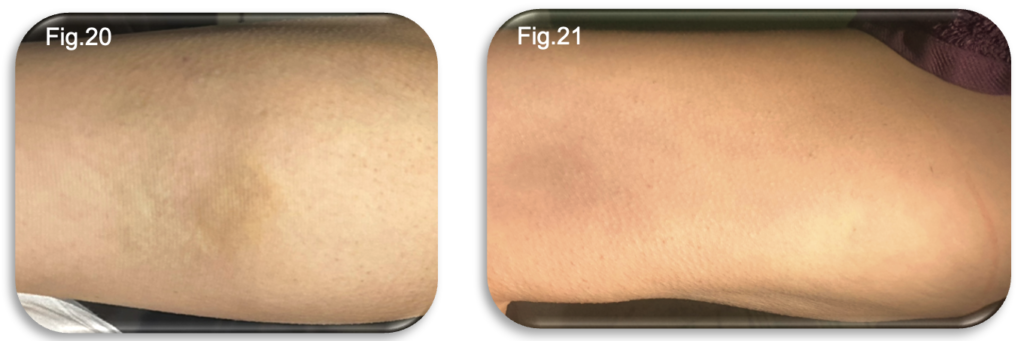

At five weeks post procedure, the patient continues to progress well, with no requirement for analgesia at any stage of recovery. Symptoms have generally improved, but some persistent thigh tightness, restlessness and evening aching remain and continues to benefit from ongoing compression hosiery. Bruising in the thigh had virtually resolved, leaving only minimal residual discolouration. However, hyperpigmentation (“staining”) along the medial lower leg, corresponding to previously treated tributaries was now more noticeable (Fig.20-21). This remains consistent with the expected resolution pattern following EVLA and UGFS, where breakdown of trapped blood products can lead to temporary pigmentation. Limited mobility during workdays was reported to exacerbate sensations of tightness and fatigue in the limb, highlighting the continued benefit of regular walking.

A new challenge emerged during this last 2 weeks, where the patient experienced increasing discomfort at the medial forefoot, specifically over the head of the first metatarsal. Although not visible, this suggested excessive pressure from the toe welt of the compression stocking. The patient’s naturally wide instep appears to have contributed to localised over tightening, producing a tendonitis type discomfort. A closed toe variant of the hosiery was ordered, and symptoms resolved completely within 48 hours of switching garments.

The patient remains active, continues her running routine, and is now approaching the scheduled vascular review in two weeks. As highlighted after three weeks, there had been a subconscious change in her gait aimed at enhancing comfort during ambulation. Although this compensatory adjustment initially proved beneficial, she has since developed a deep muscle ache. This discomfort is thought to be associated with less dominant muscle groups compensating for the altered walking style.

Patient Narrative

“I’m now five weeks on, and I still haven’t needed any painkillers at all, which I’m really pleased about. The tightness is still there, especially by the end of the day, and the leg can feel quite restless and achy if I haven’t been able to walk regularly. On busy workdays when I’m sitting for too long, it’s definitely worse. The bruising in my thigh has almost completely gone now, but the staining lower down the leg is still noticeable where the branching veins were treated. I know this is normal, so I’m not worried about it”.

“For some reason, the toe area of the stocking suddenly started causing quite a lot of discomfort, especially over the big toe. I have a wide instep, so I thought that might be making the toe section too tight. I ordered a closed toe version of the stocking, and within a day or two the pain disappeared completely, which was a huge relief”.

“Running is going well and getting easier all the time. I’m looking forward to the vascular review in two weeks, although I do feel slightly anxious, as everything is starting to feel much better now and I’m really hoping I won’t need more sclerotherapy. At the same time, I understand that if the scan suggests further treatment is needed, it will be beneficial in the long term”.

7 weeks Post Procedure: Vascular Review

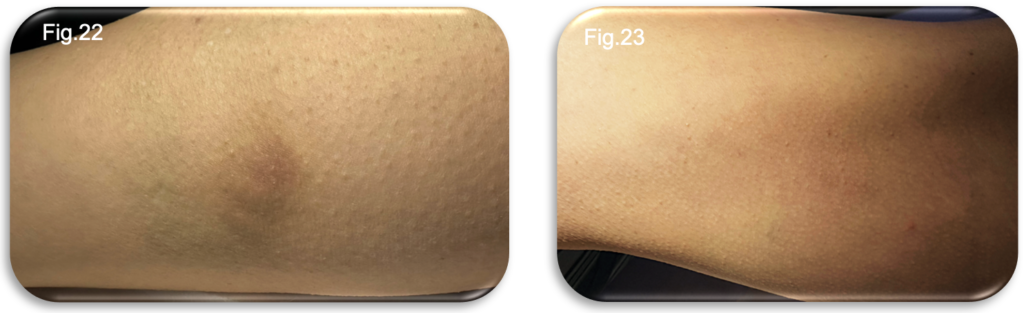

At the seven week vascular follow up appointment, bruising along the thigh had fully resolved, while mild hyperpigmentation and small palpable nodules persisted within the medial lower limb (Fig.22-23). These findings remain consistent with normal post sclerotherapy tissue response and gradual vein involution.

During the consultation, the patient provided a summary of her recovery journey, describing periods of tightness, deep aching, particularly in the evenings and overnight and the need for continuous compression wear. She also highlighted improvements in running tolerance and the gradual reduction of bruising and restlessness over recent weeks.

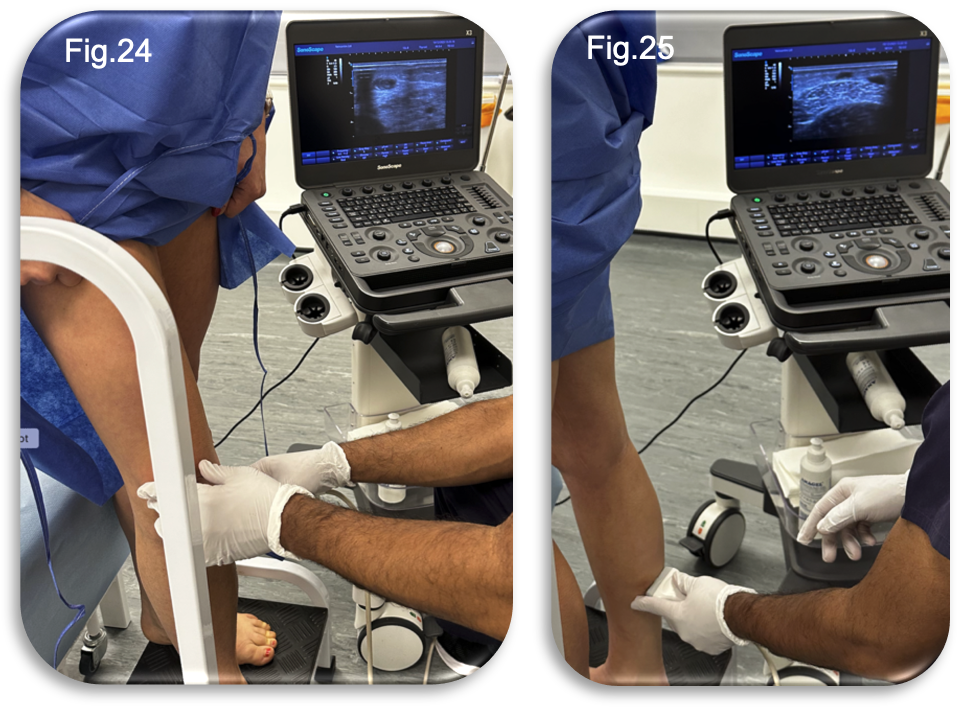

A full length duplex ultrasound scan was performed with the patient in the upright position to assess the status of the treated GSV and evaluate the necessity for further intervention (Fig 24-25). The scan confirmed complete occlusion of the GSV along its treated course, with no evidence of residual or recurrent reflux. However, a small number of medial tributaries remained patent. It was therefore advised that a further, small volume session of UGFS would be beneficial to fully occlude these residual veins and optimise long term cosmetic and symptomatic outcomes.

The UGFS was performed during the same clinic appointment, with the procedure itself lasting approximately fifteen minutes (Fig.26). Following the injections, the patient was advised to continue wearing compression hosiery for a further seven days to aid recovery and optimise treatment outcomes. Given the anatomical site of the injections, the option to switch from full length to below knee compression hosiery was discussed.

The patient was informed that below knee hosiery would be suitable and could be chosen if preferred, offering increased comfort without compromising the therapeutic effect. The procedure was well tolerated, with the patient reporting no pain or adverse effects during or after the injections. The consultant expressed a high degree of confidence that this additional treatment would complete the patient’s care pathway, signalling a positive prognosis for full resolution.

Patient Narrative

“Today was my vascular review, and it was reassuring to hear that the large vein in my leg has fully closed. I still have some staining and a few lumpy areas lower down my leg where the foam was injected, but I was told this is normal and will settle in time”.

“I talked through the recovery journey with the consultant, the ups and downs, the tightness, the restless evenings, the challenges with the stockings, but also how much things have improved over the past couple of weeks. I explained that running has been going well, and although there’s still some positional tightness and discomfort, it doesn’t stop me doing anything”.

“I was slightly disappointed, though not surprised, to be told I needed a bit more foam sclerotherapy. I expected this might happen from the advice I was given earlier, so it wasn’t a shock, just a bit disheartening when everything had started feeling much better. The extra injections were completely painless and over very quickly, and the consultant seemed very confident that this would finish the treatment”.

“That evening, my leg felt quite restless and heavy again, especially around the treated medial area. It settled a little overnight and I’m hopeful it will continue to calm down over the next few days. I have been advised to continue wearing compression stockings for another week to support the healing process. This time, I have the option to switch to below knee stockings. However, I’m comfortable continuing with my current stocking as it’s familiar and easy to manage”.

Summary

Clinical

Across the seven week recovery period, the patient demonstrated a steady and uncomplicated postoperative course following endovenous laser ablation of the GSV with adjunctive UGFS to medial tributaries. In the early phase, from 24 to 96 hours, she experienced mild tightness and heaviness along the ablation tract and a dull medial ache following UGFS. A small amount of bleeding at the catheter insertion site resolved quickly, and although bruising developed along the thigh and lower medial gaiter, there were no signs of infection, excessive swelling or concerning inflammation. Compression hosiery was well tolerated and clearly beneficial, supporting comfort and reducing restlessness. Mobility remained fully preserved, and she was able to resume short distance running without difficulty.

During the first and second week, bruising initially intensified before gradually resolving, most noticeably in the thigh region. Tightness and deep tissue aching remained more pronounced in the evenings and overnight, consistent with perivenous inflammatory changes and the natural progression of fibrosis within the treated vein. Continuous use of compression hosiery continued to alleviate symptoms. No analgesia was required at any stage, and the patient maintained full independence in daily mobility.

By week three, there was clear improvement. Bruising had markedly faded, although mild hyperpigmentation became visible along the medial aspect where tributaries had been treated. This presentation was entirely consistent with erythrocyte breakdown and vein collapse following UGFS. A firm, palpable cord was still present in the thigh, reflecting continuing fibrosis. Physical activity, including regular running was maintained without limitation.

At the five week point, almost all bruising had resolved, particularly within the thigh, while the medial staining remained visible, but was improving gradually. Tightness and positional discomfort persisted in the evenings, but symptoms were diminishing overall. A temporary challenge occurred when the toe welt of the compression hosiery caused focal pressure and irritation over the first metatarsal head; this was quickly resolved when the patient switched to a closed toe design. Otherwise, progress remained consistently positive.

At the seven week vascular review, duplex ultrasound confirmed complete occlusion of the GSV with no residual reflux. A small number of medial tributaries remained patent, and UGFS was performed during the same appointment. The procedure was brief, painless, and considered by the consultant to be the final step in completing treatment. The patient was advised to continue compression for a further week, with below knee hosiery deemed sufficient due to the location of the injections.

Patient Narrative Summary

From the patient’s perspective, recovery unfolded as a mixture of steady progress, expected discomfort, and increasing reassurance as the weeks passed. In the early days, she described mild tightness, heaviness and a deep, dull ache in the medial leg, all of which were manageable without analgesia. Showering with a waterproof sleeve (Limbo®) made daily life easier, and she was surprised at how quickly walking and even short runs became comfortable again.

During the first two weeks, she found that evenings were often the most challenging, with increased tightness and restlessness in the leg. Walking helped relieve these sensations, and wearing the compression stocking continuously brought noticeable comfort. Bruising, though at times dramatic, followed the expected pattern of darkening before fading.

By week three, she felt her leg was improving significantly. Running became easier, and while staining and palpable lumps remained, she understood these were normal features of the healing process.

At five weeks, aside from occasional tightness and some cosmetic concerns, the main difficulty was unexpected discomfort caused by the stocking’s toe welt. The problem resolved promptly once she switched to a closed toe garment. Emotionally, she felt herself moving from uncertainty to growing confidence but remained aware that additional sclerotherapy might be necessary.

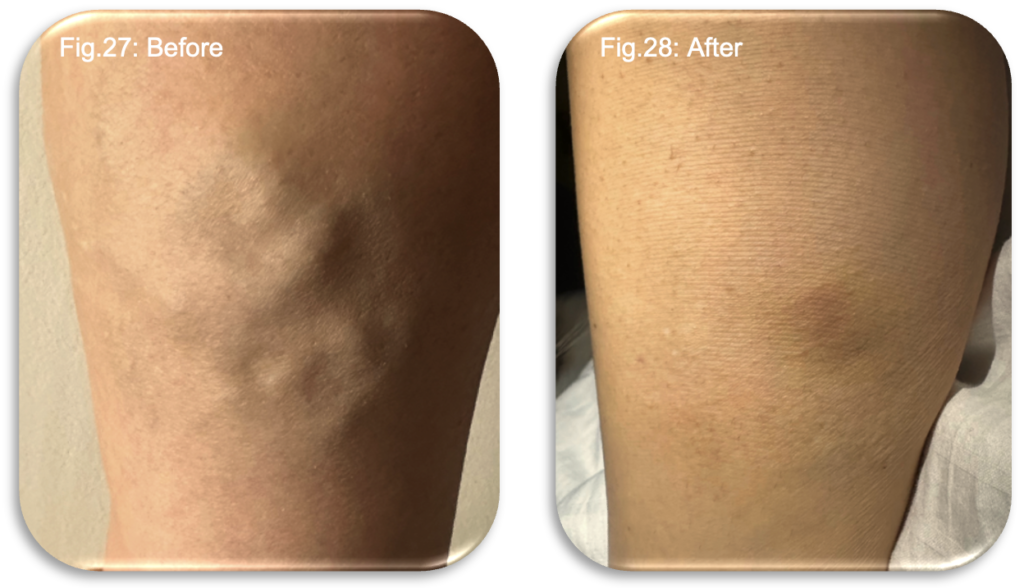

At the seven week review, she experienced a mixture of relief and mild disappointment. She was pleased to hear that the great saphenous vein had fully closed but had hoped to avoid additional treatment. Nevertheless, she accepted the rationale and found the procedure straightforward and painless. That evening, she noticed a temporary return of heaviness and restlessness in the treated medial area, but this settled overnight. Overall, she felt that the treatment pathway was reaching a positive conclusion, her symptoms and function were greatly improved and aesthetically, the changes were obvious (Fig 27-28).

Short Term Challenges with Long Term Benefits

Although the patient experienced several short term challenges, including tightness, deep aching, evening discomfort, bruising, temporary staining and practical frustrations related to compression wear, these symptoms were fully expected within the natural course of EVLA and UGFS treatment. Experiencing tightness and restlessness soon after surgery is typical and indicates normal inflammation around the veins; similarly, staining and palpable nodules are expected results of vein collapse and the breakdown of red blood cells. Even the difficulty with hosiery fit, though inconvenient, was readily resolved and did not impede recovery.

In contrast, the long term benefits of treatment are substantial. Complete occlusion of the GSV eliminates the primary source of pathological venous reflux, significantly reducing the risk of disease progression, recurrent varicosities, chronic venous insufficiency, skin changes and ulceration. Symptomatic improvements, including reduced heaviness, fatigue, aching and swelling were already evident within weeks and are expected to continue as inflammation resolves and fibrosis matures. Cosmetically, the treated limb demonstrated marked improvement, with ongoing fading of pigmentation and resolution of residual lumps anticipated over the coming months. Functionally, the patient remained fully active throughout recovery and continued running without limitation.

Thus, while short term postoperative symptoms posed understandable challenges, the long term benefits in symptom control, functional restoration and venous disease prevention were significant and durable, validating the staged approach of EVLA followed by targeted UGFS.

References

Beebe-Dimmer, J.L., Pfeifer, J.R., Engle, J.S. and Schottenfeld, D. (2005) ‘The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins’, Annals of Epidemiology, 15(3), pp. 175–184.

Brittenden, J., Cooper, D., Dimitrova, M., Scotland, G., Cotton, S.C., Elders, A., Ramsay, C.R. et al. (2019) ‘Five-year outcomes of a randomised trial of treatments for varicose veins’, New England Journal of Medicine, 380, pp. 1215–1224.

Callam, M.J. (1994) ‘Epidemiology of varicose veins’, British Journal of Surgery, 81(2), pp. 167–173.

Campbell, B., Wallace, S. and Gohel, M. (2017) ‘Variations in provision of varicose vein services in the UK’, Phlebology, 32(3), pp. 182–183.

Cavezzi, A., Labropoulos, N. and Partsch, H. (2018) ‘Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for the treatment of varicose veins’, Phlebology, 33(2), pp. 79–89.

Chang SL, Hu S, Huang YL, Lee MC, Chung WH, Cheng CY, Hsiao YC, Chang CJ, Lee SR, Chang SW, Wen YW. Treatment of Varicose Veins Affects the Incidences of Venous Thromboembolism and Peripheral Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021 Mar;14(3):e010207. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.010207. Epub 2021 Mar 9. PMID: 33685215.

Eklöf, B., Rutherford, R.B., Bergan, J.J., Carpentier, P.H., Gloviczki, P., Kistner, R.L., Meissner, M.H., Moneta, G.L., Myers, K.A., Padberg, F.T., Perrin, M., Ruckley, C.V., Smith, P.D. and Wakefield, T.W. (2004) ‘Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement’, Journal of Vascular Surgery, 40(6), pp. 1248–1252.

European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) (2022) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease.

Evans, C., Fowkes, F.G., Ruckley, C.V. and Lee, A.J. (2003) ‘Epidemiology of varicose veins’, Veins and Lymphatics, 55(2), pp. 109–114.

Gloviczki, P. and Comerota, A.J. (2017) Handbook of Venous Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. 4th edn. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Gohel, M.S., Heatley, F., Liu, X., Bradbury, A., Bulbulia, R. et al. (2018) ‘A randomised trial of early endovenous ablation in venous ulceration’, New England Journal of Medicine, 378(22), pp. 2105–2114.

Guest, J.F., Fuller, G.W. and Vowden, P. (2020) ‘Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: update from 2012/2013’, BMJ Open, 10(12), e045253. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045253.

Gupta, M., D’Souza, N., Smith, S. and Michaels, J. (2020) ‘Adjunctive sclerotherapy after endovenous ablation for varicose veins: outcomes and recommendations’, Phlebology, 35(6), pp. 413–420.

Kakkos, S.K., Nicolaides, A.N. and ESVS Guidelines Committee (2020) ‘Clinical classification and patient-reported symptoms in chronic venous disease’, Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, 8(5), pp. 789–803.

Labropoulos, N., Leon, L.R., Borge, M., Tassiopoulos, A., Giannoukas, A.D. and Gasparis, A.P. (2003) ‘Definitions for ultrasound assessment of venous reflux in lower-extremity veins’, Journal of Vascular Surgery, 38(4), pp. 793–798.

Labropoulos, N., Leon, M., Geroulakos, G. and Volteas, N. (2000) ‘The role of venous reflux and anatomic patterns of varicose veins in the clinical presentation of chronic venous insufficiency’, Journal of Vascular Surgery, 32(5), pp. 930–938.

Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Integrated Care Board (2024) Policy for Surgical Treatment of Varicose Veins. Available at: https://leicesterleicestershireandrutland.icb.nhs.uk/llr-policy-for-surgical-treatment-of-varicose-veins/ (Accessed: 26 November 2025).

Lurie, F., Passman, M., Meisner, M., Dalsing, M., Masuda, E., Welch, H., Bush, R.L., Blebea, J., Carpentier, P.H., De Maeseneer, M., Gasparis, A., Labropoulos, N., Marston, W.A., Rafetto, J., Santiago, F., Shortell, C., Uhl, J.F., Urbanek, T., van Rij, A., Eklof, B., Gloviczki, P., Kistner, R., Lawrence, P., Moneta, G., Padberg, F., Perrin, M. and Wakefield, T. (2020) ‘The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards’, Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, 8(3), pp. 342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.12.075. Erratum in: 2021, 9(1), p. 288. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.11.002. PMID: 32113854.

Marsden, G., Perry, M., Kelley, K. and Davies, A.H. (2015) ‘Diagnosis and management of varicose veins in the legs: summary of NICE guidance’, BMJ, 347, f4279.

Nandhra, S., Wallace, T., El-Sheikha, J., Leung, C., Carradice, D. and Chetter, I. (2018) ‘A randomised clinical trial of buffered tumescent local anaesthesia during endothermal ablation for superficial venous incompetence’, European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 56(5), pp. 699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.017. PMID: 30392525.

Nesbitt, C., Eifell, R.K., Coyne, P. et al. (2014) ‘Endovenous thermal ablation for varicose veins’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 7, CD010878.

Nicolaides, A., Kakkos, S., Baekgaard, N., Comerota, A., de Maeseneer, M., Eklof, B., Giannoukas, A.D., Lugli, M., Maleti, O., Myers, K., Nelzén, O., Partsch, H. and Perrin, M. (2018) ‘Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Part I’, International Angiology, 37(3), pp. 181–254. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.18.03999-8. PMID: 29871479.

NICE (2013, reaffirmed 2020) Varicose veins: diagnosis and management (CG168). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

VeinCentre (2025) Endovenous Laser Ablation (EVLA) – treatment information, VeinCentre, last reviewed 23 April 2025. Available at: https://www.veincentre.com/varicose-veins/endovenous-laser-ablation/answerpack/endovenous-laser-ablation-evla-treatment/evla-treatment-videos/can-i-have-varicose-veins-removed-with-evla/ (Accessed: 26 November 2025).

Wittens, C., Davies, A.H., Bækgaard, N., Broholm, R., Cavezzi, A., Chastanet, S., de Wolf, M., Eggen, C., Giannoukas, A., Kakkos, S., Lawson, J., Noppeney, T., Onida, S., Pittaluga, P., Thomis, S. and Toonder, I., (2015) Management of chronic venous disease of the lower limbs: Guidelines according to scientific evidence. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 49(6), pp.678–737.

Case Study 2

Skin Tear

Skin tears of the lower limb are often perceived as minor injuries, frequently resulting from simple trauma such as a knock or shear force. However, in patients with underlying venous insufficiency, fragile skin, or oedema, these seemingly small wounds can rapidly deteriorate if not recognised and managed appropriately.

This case study highlights how prompt recognition and the initiation of immediate and necessary care are critical in preventing the progression of a seemingly minor skin tear into a more serious and complex case. Early assessment and timely intervention, particularly in the presence of underlying venous insufficiency, can significantly reduce the risk of deterioration, complications and prolonged treatment, reinforcing the importance of acting early to achieve better patient outcomes.

Introduction

The patient is a 97 year-old woman who lives independently, despite having some limitations in her mobility. She manages to care for herself on a daily basis, although her movements are somewhat restricted. Her medical history includes ongoing cardiac management, for which she is prescribed warfarin, an anticoagulant medication. The use of warfarin is particularly significant, as it increases susceptibility to bleeding and can complicate healing following traumatic injuries such as skin tears. In this instance, the injury occurred when she accidentally struck her lower leg against a mobility frame, resulting in a skin tear to her lower limb.

On presentation, the patient presented with a pre tibial skin tear situated on her lower leg. The wound measured approximately 3.5 cm by 2 cm. There was a minor amount of bleeding present at the site, accompanied by a slight degree of erythema in the surrounding tissue. The patient underwent a thorough and holistic assessment to capture a complete picture of her health and vascular status. This comprehensive evaluation aimed to identify all relevant factors influencing her condition and inform subsequent care decisions. As an integral component of the assessment, her vascular status was examined by measuring the Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) using Doppler ultrasound. This procedure is crucial for assessing blood flow to the lower limbs and is instrumental in deciding the most suitable approach for managing her skin tear.

The results from the holistic review, combined with the ABPI measurement, provided a clear clinical understanding of her clinical needs. This clarity enabled the team to devise a management plan tailored specifically to the patient. In line with best practice, the immediate priority was to reassure the patient, realign the edges of the skin tear and achieve haemostasis to control bleeding.

Based on the findings of the holistic assessment, an individualised plan of care was implemented to promote healing, protect fragile skin and minimise the risk of further trauma. The wound and surrounding skin were gently cleansed to remove debris and reduce bio-burden, with care taken to avoid disruption of the skin flap. Emollient based skin care was applied to maintain skin hydration and integrity, recognising the patient’s age related skin fragility.

A protective barrier product was applied to the peri-wound area to reduce the risk of maceration and protect the surrounding skin from adhesive related trauma. A silicone faced, lightweight foam dressing with a silicone border was selected and applied to provide an optimal moist wound healing environment, ensure adequate absorption of exudate and support atraumatic removal at dressing change. The dressing was clearly labelled with the date of application and the recommended direction of removal to further reduce the risk of skin disruption when the dressing is changed.